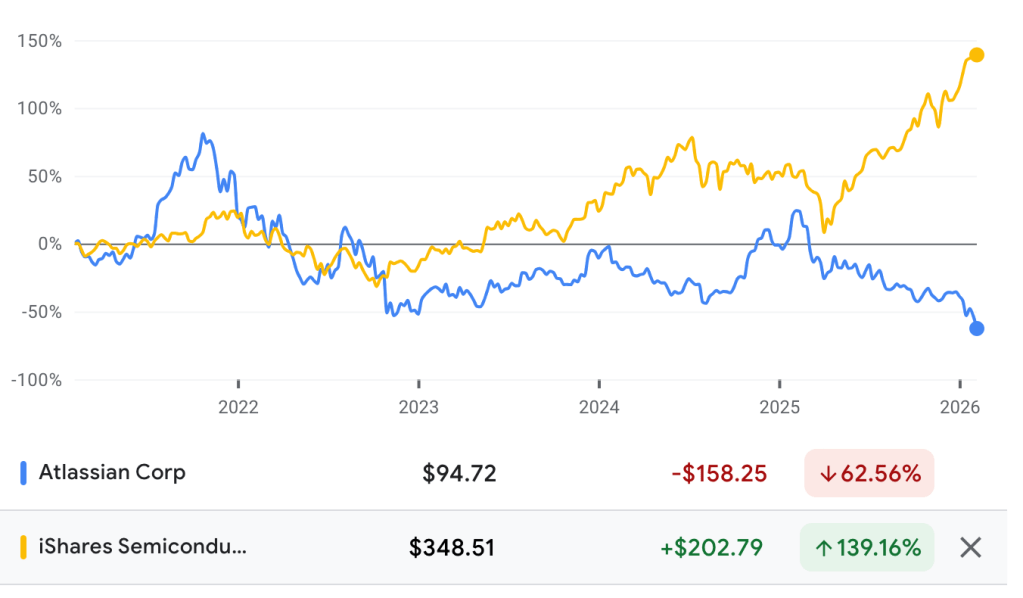

Will AI kill agile software development? Looking at Atlassian’s recent plunge suggests investors think the usual agile setup—JIRA, stories, sprint boards—could face a big disruption. That makes many wonder if the old way of working with stories and features will disappear.

At its core, agile is about evolving requirements iteratively. Stories and features aren’t the real requirements, they’re just a way for people to organise work. Even if machines write the code, we still need a clear set of goals. Those goals will still exist, but they might live somewhere else.

One option is to keep requirements inside the codebase itself, either as additional artifact or in the form of tests. Big or regulated projects will still need dedicated requirement‑management tools (for example, Polarion) to keep versions, approvals and audit trails. Those tools will keep feeding AI the context it needs while providing the governance many companies require.

AI can actually help the agile process. A product owner can give a high‑level feature description to an AI, and the AI can break it into small implementation steps (stories), write acceptance criteria and draft a first version of the code. The backlog stays, but the heavy lifting of splitting work is done by the machine, possibly asking for clarification interactively.

Whether the implementation steps will be persisted if the AI does the work and not a human will depend on our needs of observability. Since it doesn’t cost much to persist the implementation steps, I guess we will keep storing them to track progress and flag problems.

The three main parts of software delivery—requirement management, work organisation and development environments—will still be separate, but AI will tie them together more tightly. Requirement‑management platforms will keep governance, work‑organisation tools will continue to help teams prioritise and visualise work, and IDEs such as IntelliJ will still provide debugging, testing and refactoring, now with extra AI‑generated code suggestions.

Overall, AI is unlikely to kill agile — at least not yet. Instead, it will change where requirements live, how stories are created and how tools interact with each other.